Japan

Foreign affinity

After many years of travelling in and around western Europe we decided to try something different. Japan was on our list of potential destinations and we seemed to go through a phase where every second person we spoke to had been there and raved about it. So we planned a month long holiday in the northern spring.

Australians of our generation had some exposure to Japanese history and culture. It was however largely through the lens of World War II in the Pacific and post-war economic recovery. The traditions of death before surrender, ritual suicide, and harsh treatment of prisoners of war, as well as the horror of two atomic bombs dropped on civilian targets. The trade in coal and iron ore exported from Australia and importing of Japanese electrical goods and motor vehicles that went from being viewed as ‘Jap crap’ to items of high quality and prestige within a generation. Sushi for lunch.

Visiting for the first time made us realise that the impressions we carried about Japan were quite superficial and stereotyped. Being there we found it to be complex and fascinating, contradictory in some ways and straightforward in others. For us the joy of travelling in Japan is that it’s so foreign yet feels so safe and comfortable. The attention to detail is amazing, from presentation of food to timetabling of trains. The effect is somehow spiritual. And it’s a photographer’s paradise.

Shinto and Buddhist

Japan has two main religions, Shinto and Buddhism. Official statistics indicate that 70% of Japanese practise Shintoism and 70% Buddhism, suggesting that many people practise both.

Shinto is a prehistoric, animistic cult confined to Japan. Objects, places and creatures are believed to possess a distinct spiritual essence and are venerated as gods called kami. For example, Inari shrines are dedicated to the kami of rice. People visit Shinto shrines (jinja) to pay respect to the kami and pray for good fortune, during festivals, and for wedding ceremonies.

Buddhism came to Japan via China in the late 5th to early 6th C. The adaptability of Buddhism meant that rather than compete with established Shinto beliefs it coalesced with them. The Japanese call this shinbutsu-shūgō which means something like the fusion of kami and Buddhas. Buddhist temples store and display sacred objects and some still function as monasteries. Japanese people tend to have Buddhist funerals.

Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines are often built next to each other and Japanese people see no inconsistency in worshiping Buddha and Shinto kami at the same time. The shrines and temples are however strikingly different.

Shinto shrines are lively and colourful, with vermillion, white, gold and green the dominant palate. Visitors write wishes on wooden plates called ema and pick fortune telling slips called omikuji. You’ll see these on display. There are often food stalls nearby. Buddhist temples tend to be much more calm and serene, often with beautiful gardens. A raked gravel, rock, and moss garden can be sublime.

We found this combination of contrasts to be quite wondeful, and distinctively Japanese.

Shinto and Buddhist

Japan has two main religions, Shinto and Buddhism. Official statistics indicate that 70% of Japanese practise Shintoism and 70% Buddhism, suggesting that many people practise both.

Shinto is a prehistoric, animistic cult confined to Japan. Objects, places and creatures are believed to possess a distinct spiritual essence and are venerated as gods called kami. For example, Inari shrines are dedicated to the kami of rice. People visit Shinto shrines (jinja) to pay respect to the kami and pray for good fortune, during festivals, and for wedding ceremonies.

Buddhism came to Japan via China in the late 5th to early 6th C. The adaptability of Buddhism meant that rather than compete with established Shinto beliefs it coalesced with them. The Japanese call this shinbutsu-shūgō which means something like the fusion of kami and Buddhas. Buddhist temples store and display sacred objects and some still function as monasteries. Japanese people tend to have Buddhist funerals.

Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines are often built next to each other and Japanese people see no inconsistency in worshiping Buddha and Shinto kami at the same time. The shrines and temples are however strikingly different.

Shinto shrines are lively and colourful, with vermillion, white, gold and green the dominant palate. Visitors write wishes on wooden plates called ema and pick fortune telling slips called omikuji. You’ll see these on display. There are often food stalls nearby. Buddhist temples tend to be much more calm and serene, often with beautiful gardens. A raked gravel, rock, and moss garden can be sublime.

We found this combination of contrasts to be quite wondeful, and distinctively Japanese.

Modern and ancient

The interior of Japan is mountainous and not easily habitable such that most people live in cities along the coast. The urban area of Tokyo city alone is home to almost 39 million people, making it the largest city in the world.

Japan is also at high risk of natural disasters. Four of the Earth’s twelve, major tectonic plates converge in the Japanese archipelago making it prone to earthquakes and home to eleven active volcanoes. These cause tsunamis, and the Asian monsoon brings typhoons.

As a result of natural disasters, along with the impacts of war, Japan has had to build and rebuild many times over to accommodate its huge population. Its big cities are therefore very modern and Japanese architects and designers have often been at the cutting edge. The prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize has been won by eight Japanese architects since it was inaugurated in 1979.

Yet just a quick ride by shinkansen (bullet train) will take you to some place in the mountainous interior that feels ancient. Like the Buddhist monastery town of Koya-san in the Kii Mountain Range. Or the Kasugayama primeval forest in Nara where logging and hunting have been prohibited since 841.

Japan feels both modern and ancient, steeped in mysterious traditions and driven to innovate in order to survive. It’s an intoxicating mix.

Travelling in Japan

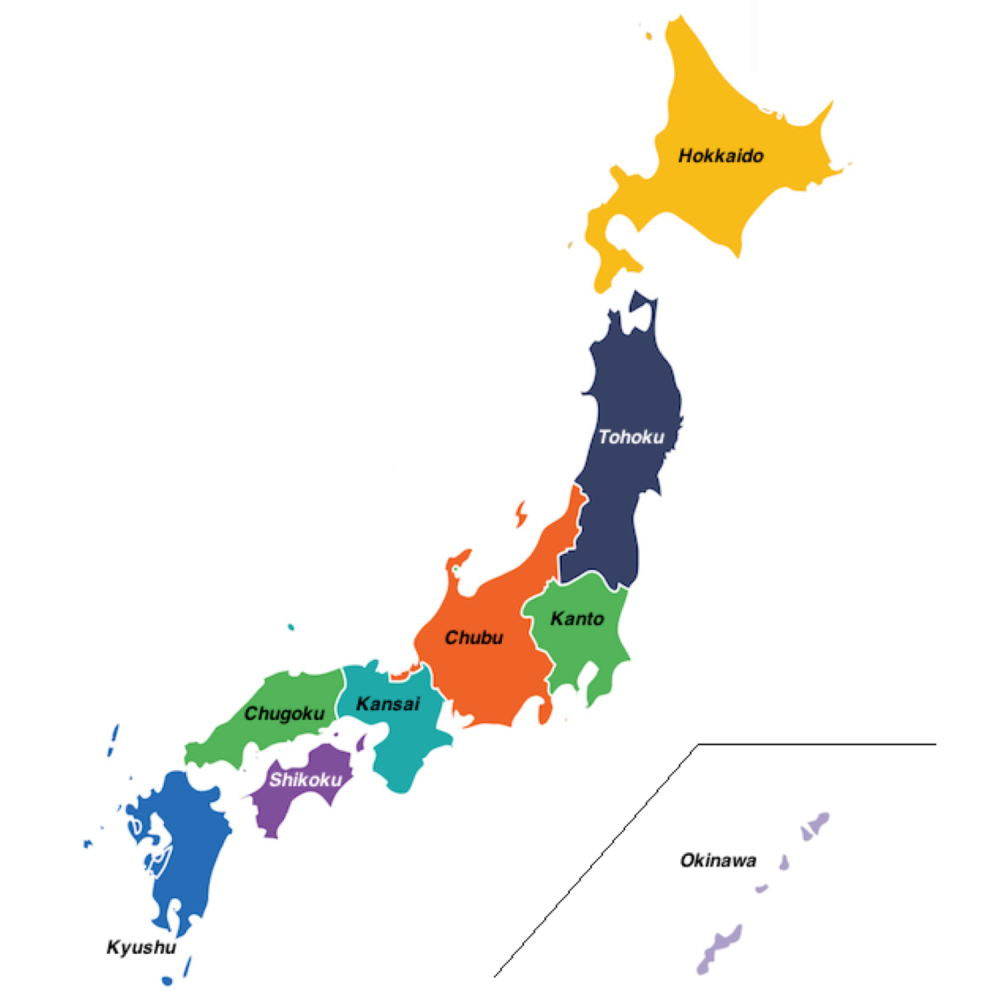

Japan has nine main regions (see coloured map). Five regions on the main island of Honshu plus Hokkaido, Shikoku, Kyushu and Okinawa. Most travel guides are organised around some variation of these. We’ve done three trips to date around central and southern Honshu, staying in 10 locations (see Google map). We hope to visit other regions in the future.

Our Experience

For the type of travelling we like to do, spring (March to May) and autumn (September to November) are our ideal seasons in Japan.

Our first visit was a month long trip around southern Honshu in the spring of 2017, experiencing the cherry blossom season and all of the culture that comes with it. We started in Tokyo and ended in Hiroshima.

The two other trips we’ve made to Japan were more opportunistic. Being based around work commitments they were constrained in terms of where and when we went, and for how long.

In the autumn of 2018 we spent eight days in Yokohama with side trips to the ancient capital of Kamakura and to Tokyo city.

In the summer of 2019 we had nine days split between Tokyo and exploring the pleasures of Nikko and its World Heritage shrines and temples.

Tokyo is only a 10.5 hour flight from Melbourne and the time difference is just two hours. For us it is well suited to more frequent, shorter visits and we hope to take full advantage of this in the future.

Our trips

While the history of Japan goes back to at least 13,000 BC, it is the cultural heritage of ~1,200 years of feudalism from 710 to 1868 that remains most visible today. There are five main periods of the feudal era and we’ve visited the major centres in which this heritage is preserved i.e. Nara, Kyoto, Kamakura, Tokyo, and Nikko.

Nara (for 85 years) and Kamakura (150 years) were both important as the capital city for shortish periods before being ‘passed over’, and so remain well preserved. Kyoto was important as the capital city for almost 1,000 years during the Heian, Muromachi and Edo periods, even after Tokugawa Ieyasu became shogun in 1600 and established his base Edo (Tokyo). It therefore has the richest cultural heritage. Not a lot of Edo period Tokyo has survived due to earthquakes, fires, wars, and development, though some fingerprints of the Tokugawa clan remain. Nikko, where Tokugawa Ieyasu is buried, has splendid heritage from this period.

The Buddhist Temples (and schools), Shinto Shrines, and Castles that we’ve visited, along with links to relevant Trip blogs, are summarised below.

- Kofuku-ji Temple (710), Hosso School. Temple moved from Kyoto.

- Todai-ji Temple (752), Kegon School. Largest wooden building in the world, housing a giant bronze Buddha.

- Sub-temples of Nigatsu-do and Sangatsu-do.

- Tamukeyama-hachimangu Shrine (749)

- Kasuga Taisha Shrine (768)

- Kencho-ji Temple (1253, Zen)

- Engaku-ji Temple (1282), Zen

- Jochi-ji Temple (1283), Zen

- Tokei-ji Temple (1285), Zen

- Tsurugaoka Shrine (1063)

- Chion-in (1600), Jodo

- Higashi Honganji (1602), Jodo-Shinsu

- Kodai-ji Temple (1606), Zen

- Kiyomizudera Temple (1633), independent

- Honen-in Temple (1680), independent

- Ni-jo Castle (1603)

- Toshogu Shrine (1617)

- Futasaran-jinja (1619)

Tokyo 2017 and Tokyo 2019

- Zojo-ji (1393), Jodo. Includes a mausoleum of Tokugawa shoguns.

- Zenkoku-ji Temple (1595), Nichiren

- Kan’ei-ji Temple (1625), Tendai. Razed in 1868 by revolutionary forces.

- Atago-jinja (1603)

- Ueno Toshugo Shrine (1651)